The Framingham Heart Study, the landmark epidemiological study of cardiovascular disease, turned 70 this past October, celebrating a milestone that it also helped many Americans reach.

There is no doubt that the results of the study have extended the lives of millions of Americans and improved the quality of life of Americans as we age. So, to celebrate February, American Heart Month, it is appropriate that we give a nod of thanks and admiration to those persistent and courageous researchers who initiated the Framingham study, and to their current-day followers who are still uncovering the secrets of heart disease.

The study results now form the foundation of our approach to heart health and are so familiar that we sometimes forget the somewhat tenuous beginnings of the effort in 1948.

Prior to World War II, the focus of medical research was controlling the spread of infectious diseases. When penicillin was introduced in 1942, physicians finally had a potent weapon that tamed scourges like pneumonia and tuberculosis. With infectious diseases comparatively under control, the focus turned to the emerging epidemic of cardiovascular disease. When President Roosevelt died prematurely at age 63 of hypertensive heart disease and stroke in 1945, national awareness of the dangers of heart disease intensified. Despite his patrician upbringing and access to the best medical care available, Roosevelt was not exempt from the ravages of poorly diagnosed and minimally treated heart disease. At the time of Roosevelt’s death, one in two Americans died from cardiovascular disease. Risk factors were poorly understood, if at all. In fact, it was not until the Framingham Study began to report its findings that the term “risk factor” was coined and widely used. But we are getting ahead of ourselves.

Three years after Roosevelt’s death, President Harry Truman signed the ‘National Heart Act.’ The act noted that the “Nation’s health is seriously threatened by diseases of the heart and circulation” and established the National Heart Institute, now the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and called for intensified research on the conditions. The initial proposal for a study to examine the causes of heart disease presciently called for an epidemiological approach that would follow the progression of the disease through clinical exams and long-term follow-up. As an indication of the lack of knowledge about the causes of heart disease, the budget for the fledgling study included “funds to buy ashtrays for the smoking needs of the study’s staff members” according to an article four years ago in The Lancet.

The study came close to being called the Paintsville Study, after Paintsville, Kentucky, the other front-runner as a locale for the work. But Framingham won, not least because of its proximity to Boston and Harvard Medical School, where many of its researchers were centered. Additionally, the people of Framingham had shown themselves to be amenable to medical research with their participation in the Framingham Tuberculosis Demonstration Study a generation earlier.

Seventy years and three generations after the first study subjects were enrolled, the Framingham Study is still making contributions to medical knowledge. Through the decades, it has broadened its research to compensate for initial missteps, adding individuals to the study to more accurately reflect the United States’ population as a whole. It has intensified its focus on the heart health of women, as heart disease remains the most frequent killer of women in the United States. And, keeping in step with and informed by related medical advances, it now studies the relationships between physical traits and genetic patterns among the study subjects.

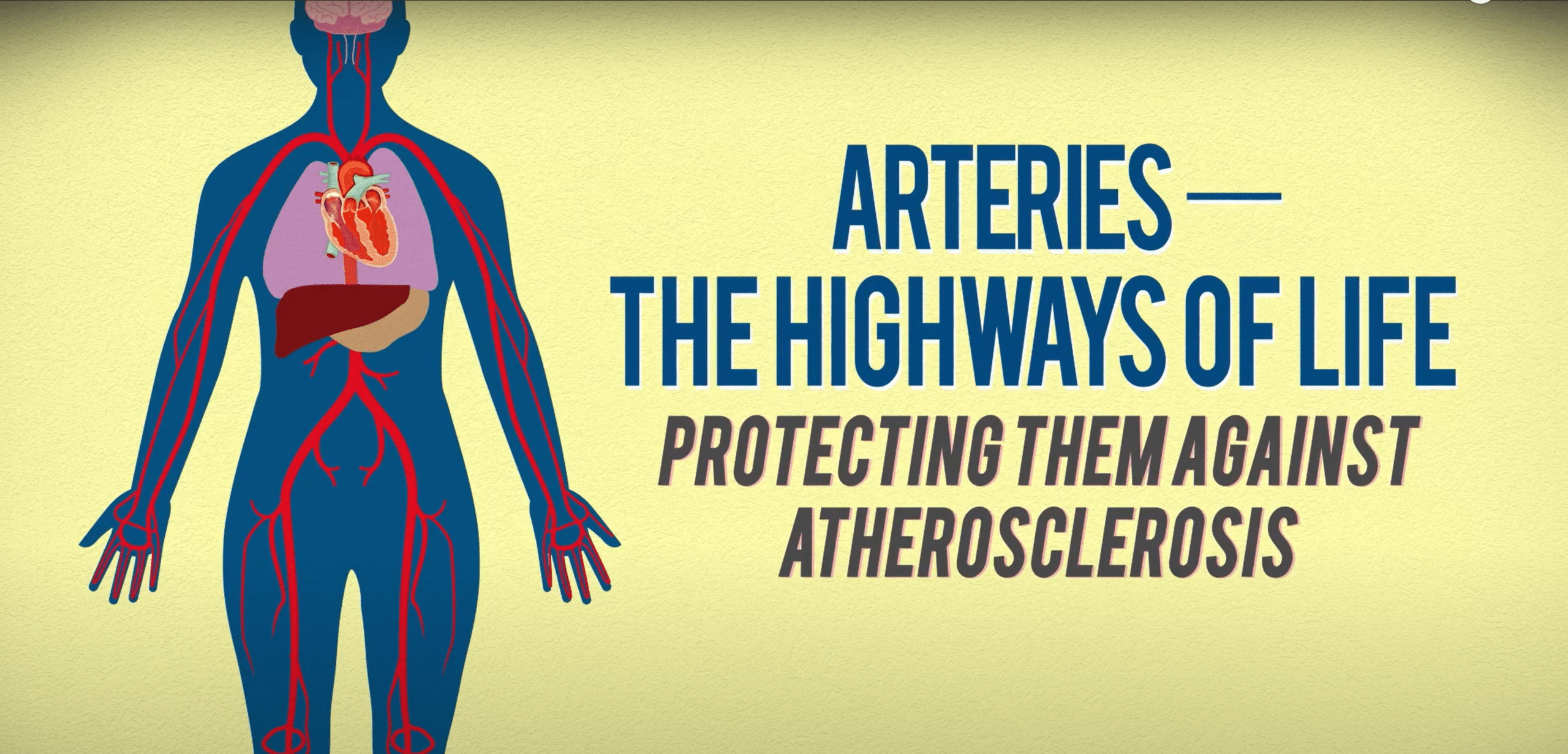

In addition to thanking the researchers who initiated the Framingham study, let’s give a quick round of thanks to our hearts. While you read this blog, your life-sustaining organ beat about 2,000 times, circulating five or six gallons of blood through your body each minute, or about 2,000 gallons per day. I’d say that deserves a special Valentine from each of us, as well as a commitment to do all we can to maintain our heart health during the coming year.