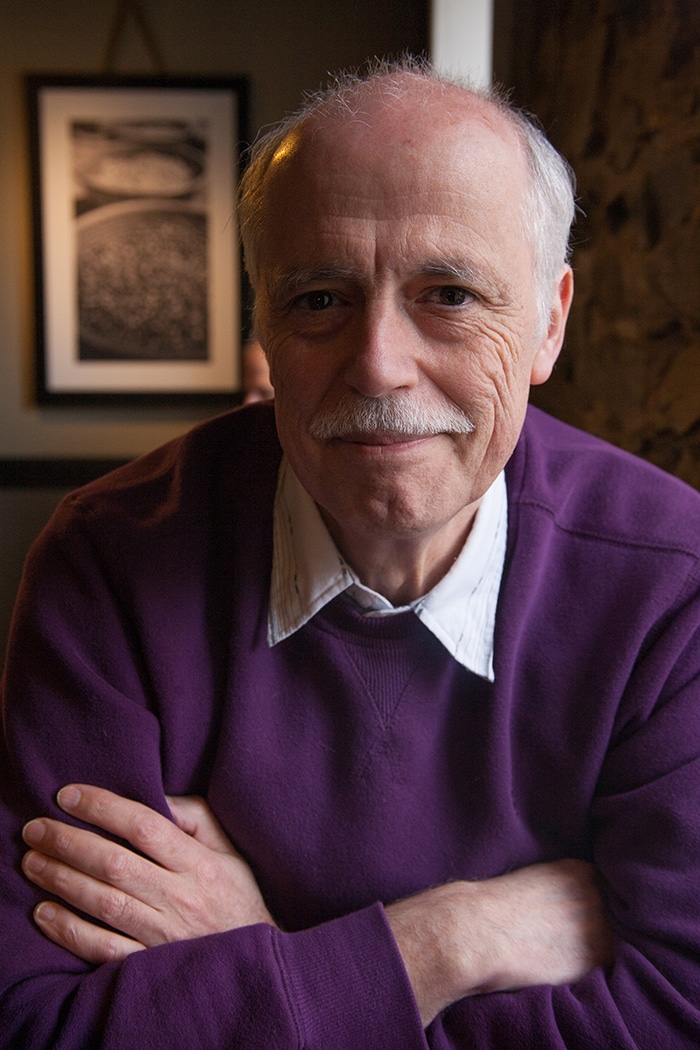

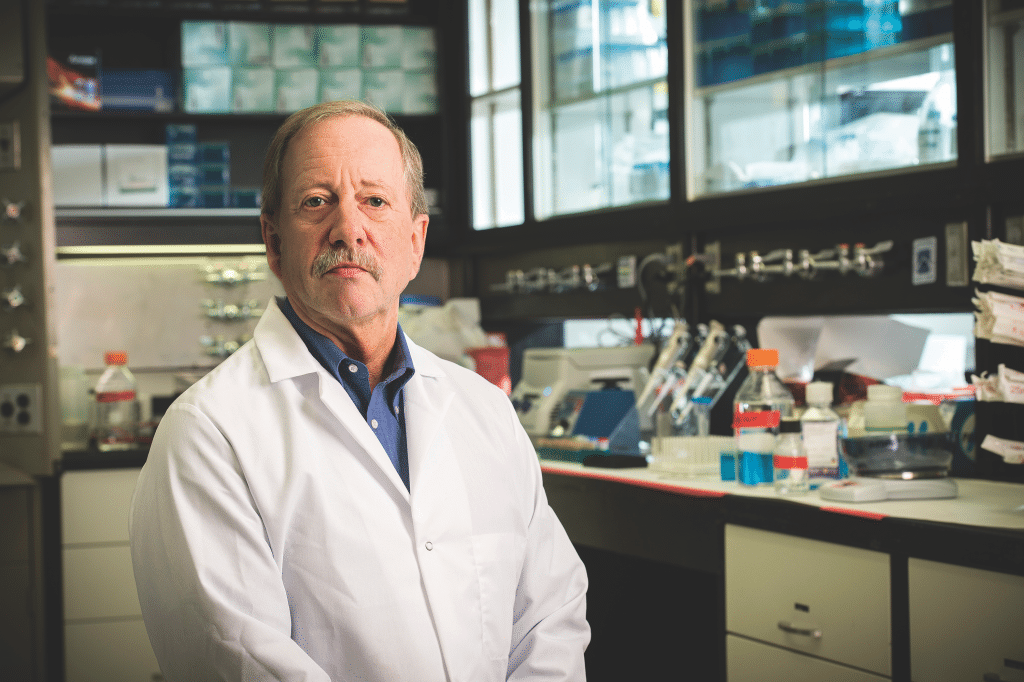

For this edition of the Healthspan Campaign Expert Q & A, we talk with Steven N. Austad, Ph.D., distinguished professor and chair of the University of Alabama at Birmingham Department of Biology, and scientific director for the American Federation for Aging Research, about his world travels, his work in the lab, and his participation in this month’s National Geographic Channel special on aging.

Q: You’ve traveled the world looking at how animals age. How did those experiences influence your current work in the lab?

SA: Well, travel always broadens one’s horizons and as one of the few researchers who has observed many different animal species aging in the wild, as well as in the lab, I think that I’ve learned mostly to be alive to unexpected possibilities that nature may present us. My current work has certainly benefited from this perspective, otherwise I could not be studying the senescence-retarding properties of long-lived clams or investigating how wild mice age.

Q: What projects are you and your team currently working on?

SA: Without question, the most exciting project my lab is working on now involves how some substances found in a long-lived (500+ years) clam species prevent protein misfolding. As misfolded proteins are involved in many aspects of aging – most obviously Alzheimer’s disease but a number of other normal aging processes as well – this finding, once we can discover what the substance is, offers an exciting and novel direction in aging research.

Q: The drug metformin has been in the news lately. What are your impressions on its potential to slow aging?

SA: Metformin is interesting in that the evidence for its senescence-retarding properties is considerably stronger for people than for traditional laboratory animals such as mice. That shouldn’t be a huge surprise. Despite what some researchers may think, mice are not small, furry, long-tailed humans. Because metformin is known to be a very safe drug, having been used in millions of people for decades to treat Type 2 diabetes, the worst case scenario is that its broad use would prevent a lot of diabetes, and, if it also has broad disease prevention properties, it will be a huge medical game-changer. Getting back to being alive to possibilities, I should point out that metformin was originally isolated from a common plant, the French lilac, and had been used in folk medicine since the Middle Ages. We can’t ignore folk wisdom. It is often wrong, but occasionally it is spectacularly right.

Q: What have your own studies taught you about aging and health? Do you think major breakthroughs are on the horizon or are we still decades away?

SA: A large program sponsored by the National Institute on Aging tests drugs for their life-extending properties in mice. Of the first 16 drugs tested, five have shown a positive effect. That is a spectacular success rate. That tells me that we now understand a number of the major destructive processes involved in aging and are learning how to mitigate them. So I’m optimistic that major breakthroughs are just around the corner. The problem is that experimentally verifying the validity of these breakthroughs in human populations takes a few years. However, it does not take decades as we previously thought.

Q: What do you hope this upcoming National Geographic Channel special, The Age of Aging, that airs on November 29 accomplishes? What was it like to be a part of it?

SA: The National Geographic Channel special will highlight the tremendous excitement that is currently electrifying the field, because we all know that we are on the verge of something huge and unprecedented in medical history. What was particularly gratifying to me to be a small part of this special was the passion of the producers to get the science right. Before I got into science, I worked in the film industry in Hollywood, and I can tell you from personal experience that filmmakers don’t often let accuracy stand in the way of telling their preconceived story. It was a real pleasure to work with the National Geographic people because accuracy was first and foremost what they were after.

Q: A side question on your Hollywood comment, what was it like training lions for the movies? Any interesting stories?

SA: It was seldom dull, that’s for sure. I have lots and lots of stories such as the time I pulled actress Melanie Griffith’s head out of a lion’s mouth or the time I accidentally ended up in a cage with a hungry, untrained lion. Whether these stories are interesting or not, I’ll leave for others to determine.

Q: What is the importance of aging research to society’s present and future well-being?

SA: If we are to save our health care system, we can’t just continue to focus on treating one disease at a time. We’ve done that, and our success – age-adjusted heart disease and stroke deaths have plunged by more than 30 percent since 2000 – ironically has led to an explosion of other societal health problems all because of aging. The number of people who are wheelchair bound, bedridden, or demented keeps rising as they no longer die from traditional diseases. It is now time to address these health problems as a group. That is the promise that basic aging research presents.