April 24 through 27 is World Immunization Week, and this year’s theme is “Protected Together: Vaccines Work!” To mark World Immunization Week, we spoke to Paul A. Offit, MD, who is the Director of the Vaccine Education Center and professor of pediatrics in the Division of Infectious Diseases at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Read our interview with him below about the importance of vaccines, and check out the Alliance for Aging Research’s resources on vaccinations here.

The theme of this year’s World Immunization Week is “Protected Together: Vaccines Work!” How do vaccines work?

Vaccines induce immunity that would be acquired by natural infection without having to pay the price of natural infection. They work in the community because when enough people are vaccinated (so-called community or herd immunity) viruses and bacteria can’t spread in a given population.

You co-invented a rotavirus vaccine. How was it made?

The strains of rotavirus that eventually became the rotavirus vaccine were made by combining human rotavirus strains with a cow rotavirus strain. The cow rotavirus strain critically lessened the capacity of these reassortant viruses to cause disease in children. We first tested the strains in mice, then adults, then progressively larger trials of children first for safety, then for efficacy.

How can people encourage their family members of all ages to get vaccinated?

I think everybody thinks they are invulnerable. Everybody thinks that it is not going to happen to them, to their children, until it does. When it does, they say, “I can’t believe this happened to me.” Then they become vigorous advocates for children’s vaccinations. That’s true for adults as well. You never think you will be the one to suffer from pneumonia. You never think you will be one of the tens of thousands of people impacted by influenza. People need to know that vaccines are safe and impactful.

You wrote a book called Bad Advice: Or Why Celebrities, Politicians, and Activists Aren’t Your Best Source of Health Information. What are some common misconceptions about vaccines that you address in your book?

I think the biggest misconceptions are that vaccines are somehow weakening or overwhelming or perturbing our immune systems—that because we are given so many vaccines, it is causing children to develop disabilities. That is the concern. But vaccines don’t do any of those things; they aren’t causing any disorders. One thing that vaccines cause is adulthood. Vaccines cause adulthood and cause you to live longer. Vaccines are allowing you to live long enough to then get some disorders, but they aren’t causing the disorders.

You are the professor of pediatric infectious diseases at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. What are some common questions you get about vaccines?

I get a lot of questions that have to do with vaccine ingredients—questions about ingredients like mercury and formaldehyde. Parents wonder if those products, which are contained in trace quantities in vaccine, are doing harm. Those are the big questions.

Recent outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases like measles have been occurring across the United States. Why are outbreaks like this particularly risky for populations like our young children and older adults?

Before there was a measles vaccine, in 1963 there were three to four million cases of measles. We’d have about 500 deaths per year from measles. Last year, we had about 380 cases of measles. Get up to a few thousand cases and you could see measles start killing children again. There is so much that we don’t know in medicine, but this we do know. Some germs can be prevented. If they can be prevented, prevent them—don’t leave your child or adult vulnerable.

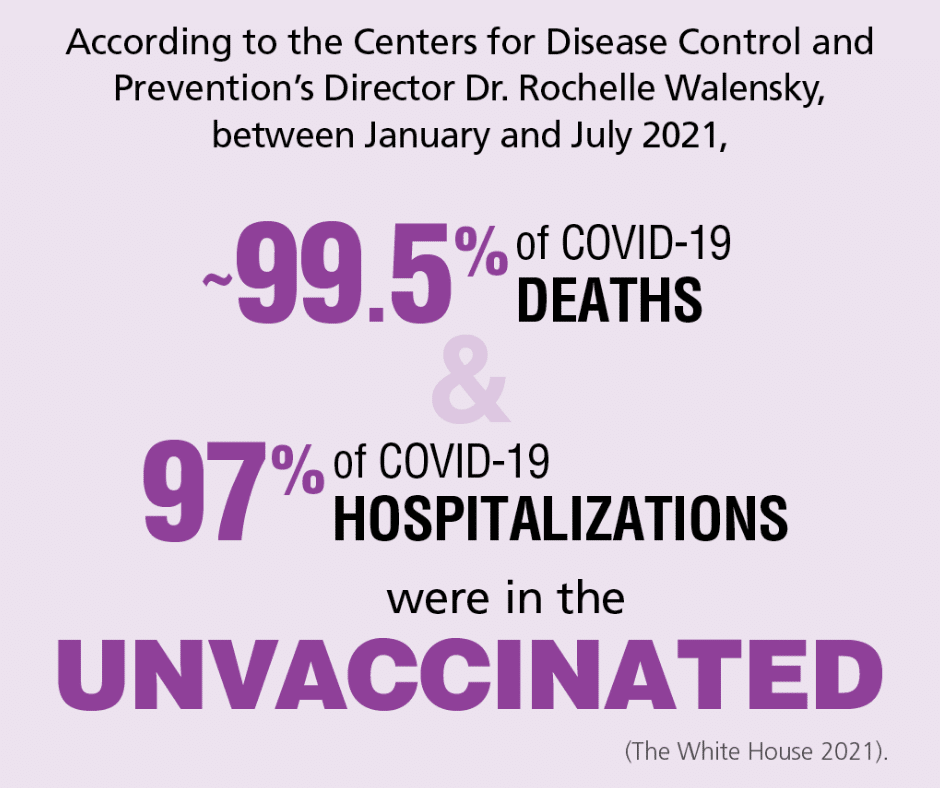

The World Health Organization named vaccine hesitancy one of the top global public health threats of 2019. How has vaccine hesitancy impacted the number of cases and outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases?

This certainly impacted the recent measles outbreak. We eliminated measles by 2000. If you look at where these outbreaks are occurring, it’s where a critical number of children are not vaccinated. That’s the story now in places like Detroit and Brooklyn. When you choose not to vaccine, your child is at risk.

Why are vaccinations also important for older adults, and what vaccinations are recommended?

Adults should receive an influenza vaccine every year. They should get diphtheria and tetanus roughly every ten years. If they didn’t receive an HPV vaccine as an adolescent, they can get it up to 45 years of age. They should get the “MMR” (measles, mumps, and rubella) vaccine if they haven’t had those diseases, as well as the pneumococcal vaccine and the chicken pox vaccine. Those are the big ones.